Not All Scotch Is Whisky: A Malt-Lover’s Guide to Scotch Ale

Not All Scotch Is Whisky: A Malt-Lover’s Guide to Scotch Ale

“You see the word Scotch on a beer label and your brain does a little flip,” I joked on the podcast. Many of us picture whisky, peat, fire and kilts. What you’re actually holding is a malt‑rich beer that never saw a barrel and doesn’t care about hops. That mix‑up is part of the charm. Scotch Ale, or Wee Heavy if you want to sound like you’ve been to a bottle share, is a misread style that deserves better. It isn’t whisky and it isn’t a smoked beer. It’s a celebration of malt, patience and history. Let’s break down where it came from, what makes it tick and how you can brew and enjoy it at home.

How the Scotch Ale Was Born

In 18th-century Edinburgh, brewers sent strong ales to the Continent and the Americas. These beers needed to travel well, so Scottish brewers made them sweet and sturdy. Local ingredients, like soft Scottish water, native barley, and even heather, gave them a smooth profile.

As brewing became industrialized in the 18th and 19th centuries, thermometers, hydrometers, and better transport allowed for standardized production and aging of beer. Pioneers like William Younger and Robert McEwan experimented with aging to bring out deeper caramel flavors. Stronger versions with more alcohol appeared. The name “Scotch Ale” was primarily used for export; at home, people referred to their beers by their strength.

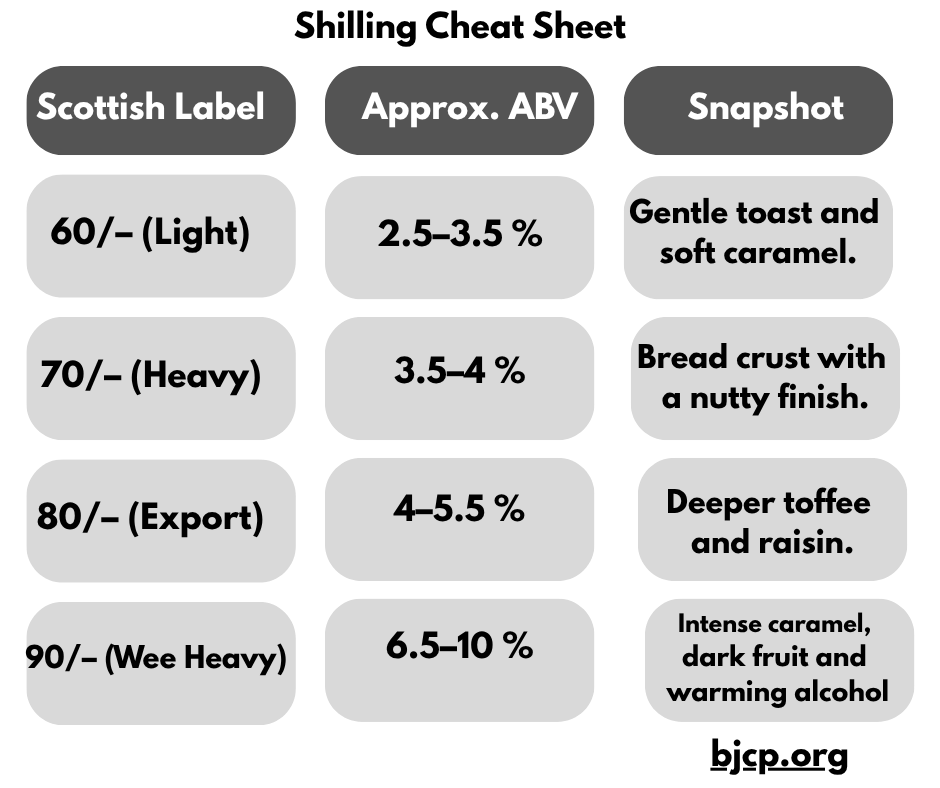

The shilling system reflected price per cask; bigger numbers meant stronger beers, even after the price link faded during the early 20th century bjcp.org

Scotch Ale and Whisky: Name Confusion

Scotch Ale and Wee Heavy are often considered the same in modern craft beer circles, and many people assume they must taste like whisky. American brewers took the old name and created big, boozy beers—eight, nine, or even ten percent—and added extra caramel malt. Beers like Founders Dirty Bastard and Oskar Blues Old Chub showcase this style: they are full of caramel and dark fruit with a hint of smoke. Some versions even add smoked malt, but smoke isn’t part of the original style.

Scotch Ale and the Smoke Myth

A long-standing myth suggests Scotch Ale should taste like a dram of Islay whisky. Brewing history tells a different story: Scottish brewers didn’t use peat-smoked malt. Peat is used in whisky distilling—distillers dry barley over peat fires, which gives the spirit its distinctive smoky flavor. Today, brewing malt is dried by coke or modern kilns. The Beer Judge Certification Program (BJCP) states that smoked malt isn’t traditional, and smoked versions fall into a different competition category.

That doesn’t mean you can’t experiment with smoke. Our own Freedom Fighter Scotch Ale kit features a touch of peated malt, allowing us to enjoy the subtle hint of smoke. We know it’s not part of the style, but that beer is too good to change now. It’s a fun twist, not a strict rule.

Malt Rules: Scotch Ale Ingredients and Flavor

A great Scotch Ale focuses on malt. Imagine caramel, toffee, toasted bread, raisins, and figs; hops are added to prevent the beer from being too sweet, but they shouldn’t dominate the flavor. Here’s what matters:

Base malt: Most of the grain should be high-quality pale malt, such as Maris Otter or Golden Promise. Add Munich or Vienna for bread-crust flavors, Crystal 60–80 °L for caramel depth, Melanoidin or Aromatic for biscuit, and a little roasted barley to darken the color.

Hop restraint: English hops, such as East Kent Goldings, Fuggles, or Styrian Goldings, provide a gentle earthiness. Bitterness typically ranges from 17 to 25 IBU.

Clean, cool fermentation: Scottish beers tend to be weaker, sweeter, and fermented at a cooler temperature than their English counterparts. Cooler fermentation reduces fruity esters, allowing the malt to take center stage.

Body: Mash in the mid-150s (°F) to create a chewy mouthfeel. Higher finishing gravities give a warming finish without becoming syrupy.

Grain & Hop Mix for 5 Gallons

70–85 % base malt (Maris Otter or Golden Promise).

5–10 % Munich or Vienna.

5–10 % Crystal 60–80 °L.

Up to 5 % Melanoidin or Aromatic.

1–2 % roasted barley.

Hops: Add East Kent Goldings, Fuggles or Styrian Goldings at the start of the boil to reach 17–25 IBU.

Clearing Up Common Myths

“It’s peaty like whisky”

No, it isn’t. Traditional recipes don’t use peat‑smoked malt. bjcp.org. Any smoke you taste is from barrel ageing or a brewer’s playful twist.

“It should be thick and syrupy.”

Wee Heavy is rich, but a good one finishes smooth. High finishing gravity gives body, but cool fermentation and yeast management keep it from sticking to your tongue. bjcp.org.

“It’s just a strong British ale”

Scotch Ale came from British old ales, yet it followed its own path. Scottish beers are weaker, sweeter, darker, and less bitter than similar English beers and ferment at a cooler temperature. bjcp.org.

Scottish vs. American Takes

| Topic | Scottish tradition | American brewpub version |

|---|---|---|

| ABV | 6–7 % for a Wee Heavy | Often 8–10 %+. |

| Fermentation | Cool and clean with low esters | Warmer. can show fruity notes. |

| Grain bill | Mostly pale malt with small amounts of crystal and roasted malts | Warmer can show fruity notes. |

| Smoke | None | Sometimes added. |

| Finish | Sweet yet clean | Heavy on specialty grains and adjunct sugars. |

Homebrewing Scotch Ale: A Project with Rewards

Why give it a try?

Few beer styles repay patience like Scotch Ale. High gravity and low hops mean this beer ages gracefully, teaching you about body, mash temperature, and conditioning. It’s also a forgiving base if you want to experiment with oak ageing or a hint of smoke.

Our All‑Grain Freedom Fighter Recipe (7.6 % ABV)

- Original gravity: 1.080; Final gravity: 1.023; IBU: 27.

- Mash: Hold at 153°F for an hour. 60 min. boil

- Use 9 lb Crisp Maris Otter

- 6 lb 2‑Row

- 10 oz Munich

- 10 oz Crystal 80

- 4 oz Caramel Munich

- 4 oz roasted barley

- 2 oz peated malt

- Hops: 2 oz Willamette (60)

- Ferment: approximately 65°F.

- Secondary: Add 4 oz of untoasted oak chips for a week or two.

- Bottle and age: Drinkable in a month, but it’s best after three to twelve months.

Extract Version (similar stats)

- Steep for 30 minutes at 150–160 °F.

- 10 oz Munich

- 10 oz Crystal 80

- 4 oz Caramel Munich

- 4 oz roasted barley

- 2 oz peated malt

- Add 9.9 lb Golden Light LME and 1 lb Pilsen DME,

- Hops: 2 oz Willamette (60)

- Ferment: approximately 65°F.

- Secondary: Add 4 oz of untoasted oak chips for a week or two.

- Bottle with priming sugar and stash it for at least a month.

- Bottle and age: Drinkable in a month, but it’s best after three to twelve months.

Tip: Use a healthy yeast starter for high-gravity brewing. Leave some headroom or use a blow-off tube, as fermentation can get lively. Taste often during oak aging. Patience matters; the beer doesn’t come together until it has sat for several weeks or months.

” I know the peated malt is not part of the style but this beer is just too good to change it just because of a style suggestion. Brew what you want. This is the way.”

Scotch Ale Food Pairing and Pouring

How to serve a Scotch Ale

Use a snifter, tulip, or nonic pint. Those shapes let you swirl and sniff. Serve at a slightly warmer temperature than fridge temperature—around 50–55 °F—so the malt sweetness can open up.

Carbonated Scotch?

Keep the carbonation moderate. Too much fizz makes the beer thin; too little and it feels flat. A gentle sparkle lifts caramel notes and dark fruit.

What to Pair with a Perfect Scotch Ale

Malt loves rich, roasted or caramelised foods. Try:

- Roasted lamb, beef, or game with herbs.

- Smoked sausage, bratwurst, or short ribs. Sweet malt balances salt and fat.

- Shepherd’s pie or Scottish meat pies.

- Aged cheddar or blue cheeses such as Stilton or Gorgonzola.

- Desserts like sticky toffee pudding, bread pudding with whisky cream, chocolate torte, or maple‑glazed pecan pie.

Or skip the food

Some of the best pairings aren’t edible. A flannel blanket, a good chair, and a second pour. This beer pairs well with quiet snowfall, fire pits, or reading darker stories. It’s a go‑to for friends who want something “strong but smooth.”

Why Slow Beer Matters

When the craft‑beer scene is full of hazy IPAs, pastry stouts, and flashy cans, Scotch Ale stands apart. It isn’t trendy. It’s malty and slow and improves with time scotbeers.com. Brewing and cellaring a Wee Heavy teaches you to pause and appreciate the process. Over time, the caramel softens, oak blends into the base, and the alcohol warms rather than burns. The beer ends up tasting like time well spent.

If you brew this style, consider making a double batch. Hide some bottles in a dark corner and forget about them. Months later, when the beer scene feels noisy and hop‑heavy, you’ll find a bottle that waited quietly. It will taste like patience, tradition, and the malty heart of Scotland.

For those who want to try our version with a hint of peat and oak, Northwest Brewers Supply offers the Freedom Fighter Scotch Ale kit in both all‑grain and extract options. You supply the patience; we’ll provide everything else.

940 S. Spruce Street

Burlington, WA. 98233

Tel. (360)-293-0424

E-Mail: brew@nwbrewers.com